“Whitney is the fattest person in our class.”

Bill didn’t even glance at the crinkled paper atop his desk. He spoke loud and clear, chin up, and with a pronunciation quality high above the rest.

It was Sunday afternoon and class as usual. I had fourteen adolescents all eagerly awaiting my arrival, though always too shy to say hello once I was there. I took roll call, working my way down the list of made up English names. They had all chosen their own names years ago during their first English lessons. Lucy, Eva, Bill, and Tony all seemed a bit old fashioned to me. It’s as if they were a generation behind.

After ten minutes of forced, dry conversation with my over-eager yet painfully shy students, I gave up inquiring about their weekends and asked them to pull out their homework from the previous week.

“Michael, can you please read me one of your sentences?” I asked of one of my stronger students.

He responded, “Brian is shorter than Tony”.

“Yes, Michael, that is correct, thank you. Brian, give me one sentence, please.”

He scrunched his face, searching for the best sentence of the ten he wrote. “Mary’s hair is shorter than Lucy’s but longer than Cici’s”.

Brian is a strong student, very intrinsically motivated. I hadn’t asked them to write complex comparative sentences, but he had tried anyway. Unable to restrain my emotion, I smiled broadly, knowing deep down that his accomplishment in writing a complex sentence was in direct correlation to my success as a teacher. I responded, “Yes, Brian, that is a wonderful sentence. Good job.”

I hadn’t been looking at Bill when he read his sentence of me being fat, or, the fattest, and I didn’t look in his direction then. I often pace, listening intently to their responses, seeking out small mistakes I can help them to correct. In the moment, I paused, mid-step, keeping my gaze down toward the floor. I smiled slyly, grimaced to myself and responded to his fat comment in the only manner appropriate.

“Yes, Bill, that is a perfect sentence. Thank you.”

Being fat in China isn’t the same as being fat in western cultures. I’ve been fat in my life. I am able to look into the mirror and gage whether ‘fat’ is really an appropriate adjective to use for myself. At this point in my life, it wasn’t.

I had known this word was thrown around quite freely in China, but it wasn’t until two weeks prior to this event that I understood why. I was a student in an intermediate oral communication class at the Chinese University. I was preparing the mental shift from English to Chinese for my morning lesson when my teacher, chuckling behind his podium, began class a few minutes early.

“Let me tell you a story,” he began, speaking Chinese. “I had an American student a few years ago. One day, before class, I told him he had become a little fat since arriving in China,” he paused, searching our expressions, making sure we were following along. I pursed my lips, holding back a knowing grin, and nodded for him to go on.

He continued, “The student hesitated, and said, in a hushed voice, ‘Teacher, I’m sorry, but in America, it’s not very respectful to call people fat.’”

I looked nonchalantly around the classroom. Half my classmates were Asian, their faces remained emotionless. The other half, nodding in agreement, began shuffling papers, fiddling with their dictionaries, embarrassed to admit this was indeed true. You shouldn’t call people fat.

Our teacher didn’t lack experience. He had lived abroad, he knew. Chuckling, gazing into the empty corner of the classroom, he too was embarrassed. But, he continued, wanting us to understand that Chinese people don’t intend to offend or hurt feelings. He stood up quickly, black marker in hand, and began scribbling Chinese characters on the board.

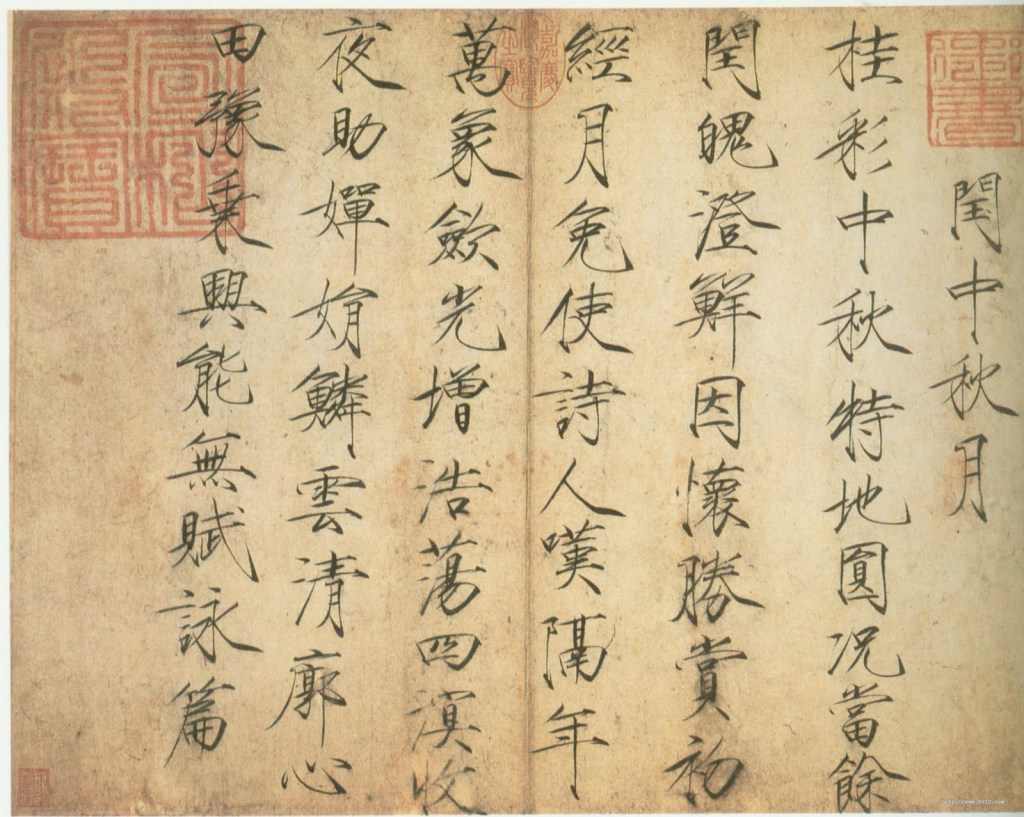

The difference lies in our perception of the word. Every Chinese character has a radical, a simple character squished into a more complex character. It serves as a clue to categorize characters, often giving the reader a sense of its meaning before they have actually learned it.

This radical, “女” , signifies woman and is squished to the left of these three characters: 妈, 好, 姐. These three characters, all related to ‘woman’, are mother, good, and sister, respectively.

This radical, “疒”, is meaningless alone, but hints at sickness, disease, or pain when inserted around the edges of these characters: 瘦, 病, 症, 疼, 痛. The first character, thin, shares the same radical as ill, disease, sore, and ache.

In America, fat is attributed to laziness or disrespect for your body. It is assumed that fat people make unhealthy choices in their life and that they don’t engage in physical activity.

These four characters all have the radical “月” on the left, which, as a radical, signifies meat: 膀, 腿, 肚子, 胖. Grouped along with shoulder, leg, and stomach, is the character for fat.

In China, fat is attributed to health and prosperity. Being labeled fat in China is far from an insult. It is acknowledgement from some, envy from others, that you are fortunate enough to eat meat on a regular basis and in abundant portions.

Maybe it’s not so bad after all to be the fattest person in the class.